What is a "plot" and why "subplots" don't exist

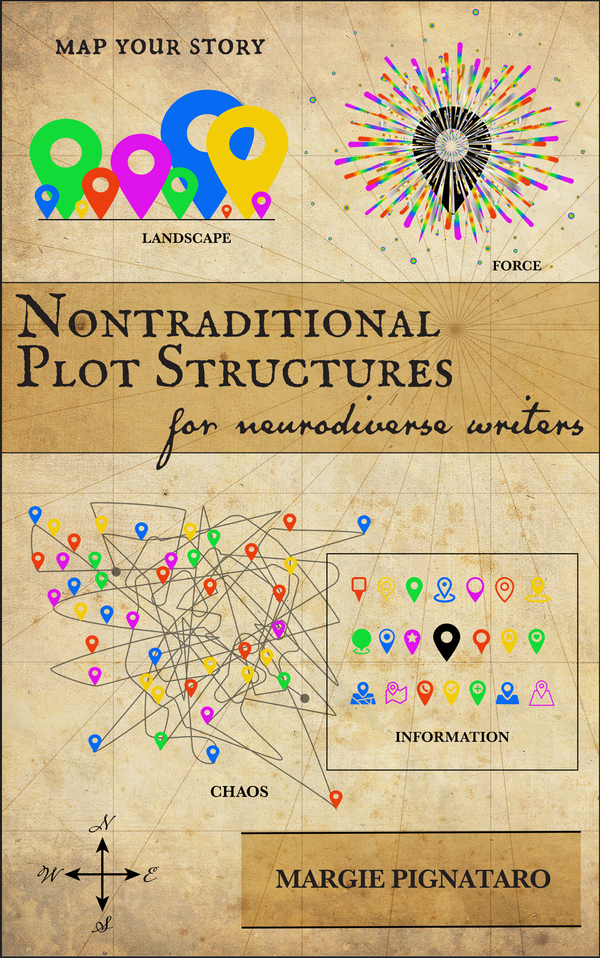

The following is a section from my upcoming free ebook Nontraditional Plot Structures for Neurodiverse writers. It comes out May 1 and will be available on this blog!

WHAT IS A "PLOT"?

This may seem like an unnecessary section. Any writer who chooses to read this book already knows what a plot is, and can probably explain it in great detail. I feel the need to go into this detail in order to support my assertions, which can seem at times strange. I come from an educational background which considered nontraditional writing to be experimental (high chance of failure), fringe (has an adolescent desire to shock), and questionable (people get offended). It’s important for me to cover all ground, not so that you know what I’m talking about, but that you know that I know what I’m talking about.

Bear with me: I shall begin with the etymology of “plot”:

Late Old English plot, “small piece of ground of defined shape,” a word of unknown origin. The sense of “ground plan,” and thus “map, chart, survey of a field, farm, etc.” is from 1550s.

Etymonline, plot

The first instances of the word “plot” are ground in the ground: it refers to a particularly defined shape of ground. This isn’t a natural shape; it’s a shape made by humans. It is a physical thing.

Plot, like our friend “journey”, eventually expanded outside its physical definitions and adopted a more complex, even artistic form: a map or survey of a piece of land. Plot had moved from the physical world into a concept, with a language of symbols and terms to describe it. A visual plot document reflects the physical world and gives it authority or value. It translates the physical world onto paper.

The meaning “a secret, plan, fully formulated scheme” (usually to accomplish some evil purpose) is from 1580s. OED says “The usage probably became widely known in connexion with the ‘Gunpowder Plot.’ “

Plot develops an “evil purpose” from the 1580s, most likely in connection with the “Gunpowder Plot” to blow up Parliament.

Plot now leaves the physical world behind, though the original physical description still is used. A plot is now an abstract idea and has nothing to do with land. It’s grounded in philosophy, morality, and, by extension, danger and violence.

I’d hazard to say that with this new denotation for the word, it also gained an air of intrigue, drama, excitement, dread, fear. It’s no wonder that by the 1640s “plot” took on meaning in literature and drama:

The meaning “set of events in a story, play, novel, etc.” is from 1640s.

Plot-line (n.) “main features of a story” is attested by 1940; earlier, in theater, “a sentence containing matter essential to the comprehension of the play’s story” (1907).

These story-telling definitions have been used only when speaking of a story, play, or novel. No one talks about the plot structure of a poem, a sculpture, or a meme. At this point in dramatic and literary history, a plot had specific elements that were unique to stories, plays, and novels: characters and action. Scholars used Aristotle’s model as the Bible of good writing.

Stories had to involve people experiencing conflict in a world we all agree exists. (Nontraditional stories, by contrast, involve people experiencing a world that not all of us agrees exists.)

There is no reason why the word plot could broaden to include nonfiction texts. The original definition based in a physical reality established a core idea that seeped through hundreds of years of use of this word: a thoughtful plan created by a human being.

I will use “plot” to describe texts of various forms, such as sculpture and paintings. I’ve never heard of anyone referring to a sculpture as having a plot, but it does. All art has a story. If it has a story, it must have a plan.

Plots have plot points. Each point is an event that causes the story to grow. I could say the plot “advances”, but that’s a very linear term. Most of the plot structures in this book gravitate away from the linear. Stories are more like living things that grow and mutate or evolve in different directions. Think of it in terms of the expansion of the universe. Everything moves outward rather than on a narrow path.

I learned in grad school that only after the climax does the story change in a significant way: everything that happens after is entirely different than what came before. This is too limited.

Each plot point is an event that changes the story in some way. Once the story begins, nothing that happens after the point is the same as before.

I DON’T BELIEVE IN SUBPLOTS

A “subplot” is a “subordinate” plot in fiction. “Subordinate” is an inferior position and in control of an authority. This isn’t the appropriate attitude toward a subplot. What this reflects is that the “plot” is more important than anything else happening in the text, and the subplots work to bolster the main plot.

I will not be using the term “subplot”. I don’t see any plot submissive to any other. Nor do I believe a text has any one, singular, important plot.

When I use the word “plot” I’m referring solely to the structure of the story: what events happen when. The story itself may have different tributaries and streams that diverge from the main focus, if one exists, but those machinations don’t apply here.

From what I’ve observed through all the texts I’ve studied, (visual arts, novels, films, plays, etc.) a text generally has three plot structures. They are not ranked in importance.

Traditional stories that have Journey plot structures also have, at least, two other plot structures. We generally label them as a “theme” or “device”. The ‘isms, such as surrealism and impressionism, make things even more complicated. The vocabulary can be very confusing and contradictory. I find most creative writing instruction and guides confusing.

It’s much easier to understand and edit a text if one acknowledges how the plots work together as a machine, simultaneously. One plot doesn’t break from everything else happening in the text. They work together by establishing plot points, events in the story which cause it to change. The plots work in conjunction, and through their combination they create something more than the three plots in themselves.

A deeper understanding of this phenomena is in the idea of Emergence:

In philosophy, systems theory, science, and art, emergence occurs when a complex entity has properties or behaviors that its parts do not have on their own, and emerge only when they interact in a wider whole.

Emergence, Wikipedia

Emergence is about creating something new as a direct and unique result of the parts interacting. This new something couldn’t have existed without the parts working together.

When the plots interact, the story is a product of Emergence. Merging plots will also be greater than the sum of its parts: multiple plot structures create a more nuanced, textured, fascinating text.

The really mind-bendy part is that the plot structures Emerge from the story.

All of this I’ll explore further in the second edition.